"Learning From UCLA"

Jyllian N. Kemsley

August 3, 2009Chemical & Engineering News

ISSN 0009-2347

Copyright © 2009 American Chemical SocietyOn January 16, Sheharbano (Sheri) Sangji, a 23-year-old chemistry research assistant, died from injuries sustained in a chemical fire on Dec. 29, 2008, in a laboratory at the University of California, Los Angeles. The incident has trained a spotlight on safety practices in academic labs, highlighting the need for awareness of risks and regular hazard assessments.

|

|

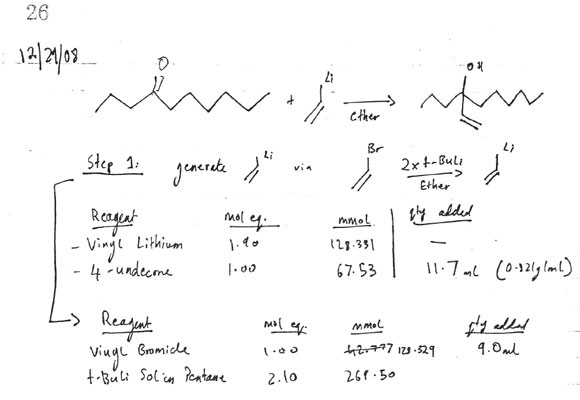

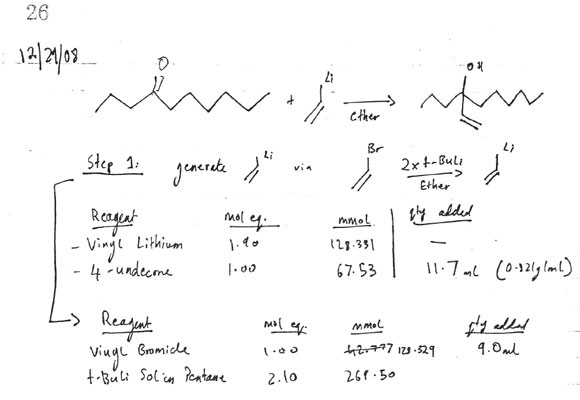

Sangji had started work in the lab of Patrick Harran, a chemistry professor at UCLA, on Oct. 13, 2008. According to copies of Sangji’s lab notebook obtained from UCLA through a California Public Records Act request, Sangji planned in December to scale up a reaction she’d run once before, on Oct. 17, to produce 4-hydroxy-4-vinyldecane from either 4-undecanone or 4-decanone. The first step of that reaction was to generate vinyllithium by reacting vinylbromide with two equivalents of tert-butyllithium (tBuLi), a pyrophoric chemical that ignites spontaneously in air.

Sangji was working on a nitrogen manifold in a fume hood in a lab on the fourth floor of UCLA’s Molecular Sciences Building. She had titrated the tBuLi twice to determine its concentration—1.69 M—and needed 159.5 mL of the reagent to react with 9.0 mL of vinyl bromide. She was drawing up the tBuLi in roughly 50-mL aliquots in a 60-mL plastic syringe equipped with a 1.5-inch, 20-gauge needle. For unknown reasons, the syringe plunger came out of the barrel and the tBuLi was exposed to the atmosphere. Although it wasn’t part of her experiment, an open flask of hexane was also in the hood and Sangji knocked it over. The tBuLi ignited and the solvent caught fire, as did Sangji’s clothes. She was wearing nitrile gloves, no lab coat, and no one remembers if she was wearing eye protection.

Although there was a safety shower in the lab, Sangji did not use it. Instead, Wei-feng Chen, a postdoctoral researcher in Harran’s group who was cleaning up one of the lab’s benches, wrapped a lab coat around Sangji to try to put out the fire. “She was screaming and was moving around and I was attempting to wrap her tightly,” Chen told Cal/OSHA Investigator Ramon Porras. Chen abandoned the lab coat when it started burning. He then started pouring water on Sangji from a nearby sink, while she sat on the floor.

Hui Ding, a postdoctoral researcher in an adjacent lab, heard Sangji screaming. He went into the lab and saw Chen trying to put out the fire. Ding also saw that “the tip of the reagent bottle was positioned sideways and was also on fire,” he told Porras. Ding returned to his lab and called 911, then checked on Chen and Sangji again before going to get Harran from his office on the floor above. When Ding returned to the lab with Harran, Harran saw that Sangji’s hands, torso, and neck were burned. “Her clothing from the waist up was largely burned off and large blisters were forming on her abdomen and hands—the skin seemed to be separating from her hands,” he told Porras in an e-mail. Sangji was conscious, asking for more water, where emergency responders were, and for someone to call her roommates. When Harran heard sirens, he went down to the road to tell the emergency personnel where they needed to go.

UCLA police dispatch recorded the 911 call at 2:54 PM as an “unknown type chemical fire.” Emergency crews were dispatched at 2:57 PM, and Christopher Lutton, a UCLA deputy fire marshal; a fire engine; and emergency medical personnel arrived at the building at 3:01 PM. Lutton donned full protective gear and went up to the lab to assess the situation, with dispatch recording at 3:06 PM that the fire was out upon arrival. Lutton cleared the other emergency responders to go up to the lab. Once medical personnel arrived, Sangji was put on a rolling chair and moved under the safety shower for decontamination. She was then transported to UCLA Ronald Reagan Medical Center. From there she was transferred to Grossman Burn Center, in Sherman Oaks, Calif., where she died on Jan. 16.Robert M. Waymouth, a chemistry professor at Stanford University, emphasizes that evaluating safety risks needs to be a constant and ongoing thing. Safety shouldn’t be something done at a training seminar and then forgotten, he says. It is critical that everyone understands the “need to make sure that there’s an awareness in the real day-to-day environment about what’s the best way to do things safely,” he says. “You need to establish a safety environment where people can encourage others to have safe practices and not be embarrassed about it.”

And just as essential, lab workers “have to have the mind-set that something can always go wrong,” Waymouth says. “If you have thought about it beforehand, you will be more prepared to deal with it. If you’re surprised, then it is more difficult to respond rationally. A prepared mind is the most important safety attitude that you can have.”